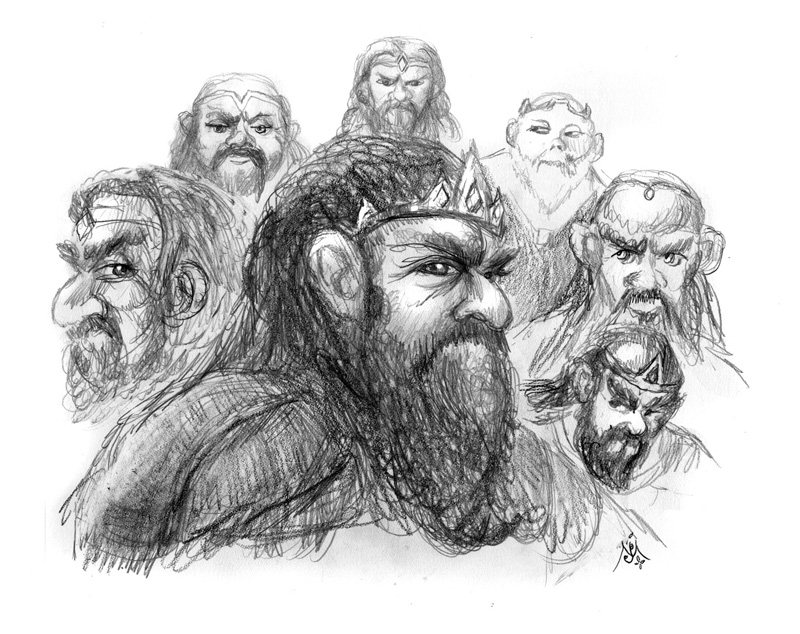

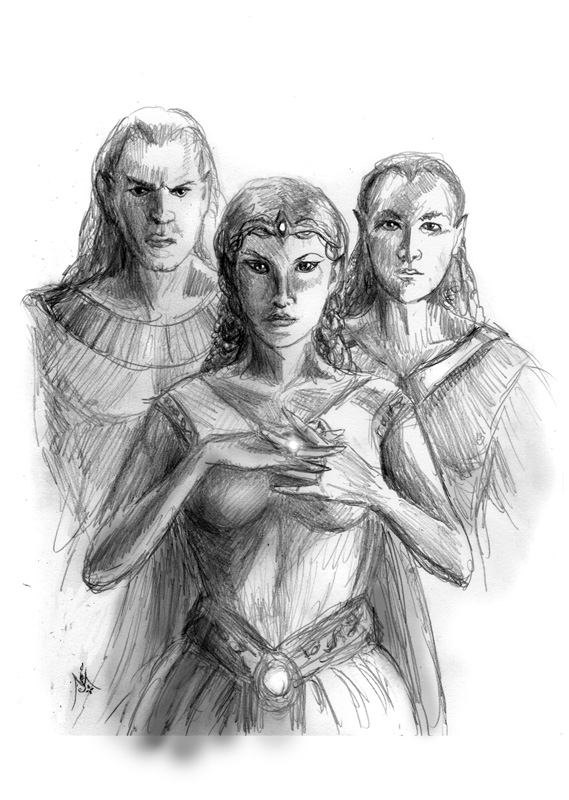

Three Rings for the Elven Kings Under the Sky….

Echoes on the Road, Study (Sam, Frodo, and Pippin)

Mystical Realms Newsletter for May, 2014

Greetings!

And welcome to my newsletter for May, 2014! Please feel free to forward this to anyone you think would be interested in keeping up with me! To receive these newsletters regularly, please drop me an email or subscribe online from my website (http://www.JefMurray.com ) or at: http://groups.google.com/group/Mystical_Realms .

Pitchers ===============

• I’ve added 2 new painting images to my website at www.JefMurray.com . These include La Belle et la Bête and The Knighting of Gimli. The first of these can be found in my Fairy Tales gallery, and the second can be found in my Middle-earth -> The Third Age -> Lord of the Rings gallery. You can also find them all by going to http://www.JefMurray.com and clicking on the “Newest Works->Paintings” link at the top, left.

• In addition to the three paintings, I have added four new graphite sketch images to the Middle-earth, Fairy Tale, and Soul & Spirit sketch galleries. You can see all of the latest together by clicking on the “Newest Works -> Sketches” link at the top, left my home page, www.JefMurray.com .

• A new, revised, and expanded edition of Seer: A Wizard’s Journal has been announced and will be available for sale very soon! The 2nd edition of this collection of tales, poetry, images and reflections sports a new cover, many interior illustrations that are now reproduced in full colour, plus two “follow on” tales to the opening story, The Watchman, that more fully introduce characters that appear regularly throughout the remainder of the book. For more information, see: http://olorispublishing.mymiddleearth.com/2014/03/25/oloris-publishing-announces-expanded-version-of-seer-a-wizards-journal-by-jef-murray/

Prospects ===================

• The game is on for Tolkien fans in Kentucky! A Long Expected Party 3 (acronym AL3P) is completely booked, but you can still be put on the waiting list for lodgings on-site. You can also stay off-site and still register and join us. I’m delighted to announce that I will be one of three guests at the event, along with Dr. Michael Drout and Dr. Amy Sturgis. For more information, see: http://www.alep-ky.us/

Ponderings ==============

“Do you think she’ll come back?”

The two girls sat huddled beneath the eaves of the forest. The unsettled breezes of the last day of April stirred the dogwood boughs, mottling the light of the newly-risen full moon. The gusts of damp air moved on, lifting branches and scattering oak catkins throughout the valley below them.

“I don’t think she’ll have much of a choice,” said the older girl. Her name was Megan.

“What do you mean?” Polly looked up at her sister. She scratched at the first mosquito bite of the season.

“Well, Elves are magical, aren’t they?”

“Sure,” said Polly.

“Well, when we saw her, she was dancing in the moonlight, right?”

“Right.”

“And it’s May Eve, right?”

“So?”

“So…whoever sees one of the Fair Folk on Beltane always gets a wish.”

“Are you sure?”

“Of course!” said Megan. “You’re so stupid…you don’t know anything! Everybody knows you get a wish if you see a Fairy on May Eve!!!”

Polly rolled her eyes. “Well, then, what are you going to wish for?”

“I don’t know yet. More wishes, maybe…”

“I don’t think that’s allowed….”

“What do you know?! I’m going to ask for enough wishes that I can become Queen!”

“There is no Queen!”

“Well, there will be, once I’ve got my wishes! And then I’ll have the finest husband, and all the jewels and clothes I could ever want!”

“What if the Elf doesn’t want you to have all those things? What if they’re not good for you?”

“She’ll have no choice. They’re my wishes, after all! And what do you mean, not good for me?! What could be better than my being able to decide what’s right and what’s wrong? Why, I shall be the wisest woman in all the world! I’ll be wiser than King Solomon! I will decide the fate of all!!!”

“What if someone doesn’t want you to decide their fate?”

“Well, they’ll have no choice! Once I have my wishes, my will shall prevail!” Megan’s eyes gleamed as she looked eagerly toward the glade where they had seen the Elf maiden dancing.

Polly sighed and shifted away from her sister. “You were right,” she said, whispering so that her sister couldn’t hear.

A chiming, silvery voice answered her from the shadows of the oak tree beside her. “Yes, but there is no helping it; she is right. A wish must be granted; it is May Eve.”

“Must it be my sister’s wish?”

“You each get a wish, because you both saw me in the glade.”

Polly thought for a moment. “Could my wish be that we had never seen you in the glade?”

There was a pause, and all Polly could hear was crickets tuning up for their evening serenade. But then came a peal of merry laughter from the shadows.

“Yes, of course!” came the answer. “But, your sister would still be granted a wish, regardless.”

Polly thought for a moment. “OK, then that’s what I’d like to wish for…that we had never seen you tonight.”

o o o

“I hate these things!” said Megan, slapping at her neck.

“What things?!” asked Polly. She felt disoriented…dizzy, even.

“The mosquitoes of course!” Megan slapped again at her neck. “And I’m tired of waiting for Fairies! I’m going in!” She stood up and brushed herself off.

“So you don’t think they’re going to come at all?” asked Polly.

“I don’t care if they do! I’m going home!”

“OK,” said Polly, standing up as well. “I’ll come too….”

“Ouch!” said Megan. “These mosquitoes are awful! I wish we’d have just one summer without them!”

Polly didn’t remember anything significant about her sister’s comment until summer ended that year. It was in autumn that it occurred to her that the only mosquito bites she and her sister had gotten all year long had been on May Eve.

May Eve

May Eve by Jef Murray

“Do you think she’ll come back?”

The two girls sat huddled beneath the eaves of the forest. The unsettled breezes of the last day of April stirred the dogwood boughs, mottling the light of the newly-risen full moon. The gusts of damp air moved on, lifting branches and scattering oak catkins throughout the valley below them.

“I don’t think she’ll have much of a choice,” said the older girl. Her name was Megan.

“What do you mean?” Polly looked up at her sister. She scratched at the first mosquito bite of the season.

“Well, Elves are magical, aren’t they?”

“Sure,” said Polly.

“Well, when we saw her, she was dancing in the moonlight, right?”

“Right.”

“And it’s May Eve, right?”

“So?”

“So…whoever sees one of the Fair Folk on Beltane always gets a wish.”

“Are you sure?”

“Of course!” said Megan. “You’re so stupid…you don’t know anything! Everybody knows you get a wish if you see a Fairy on May Eve!!!”

Polly rolled her eyes. “Well, then, what are you going to wish for?”

“I don’t know yet. More wishes, maybe…”

“I don’t think that’s allowed….”

“What do you know?! I’m going to ask for enough wishes that I can become Queen!”

“There is no Queen!”

“Well, there will be, once I’ve got my wishes! And then I’ll have the finest husband, and all the jewels and clothes I could ever want!”

“What if the Elf doesn’t want you to have all those things? What if they’re not good for you?”

“She’ll have no choice. They’re my wishes, after all! And what do you mean, not good for me?! What could be better than my being able to decide what’s right and what’s wrong? Why, I shall be the wisest woman in all the world! I’ll be wiser than King Solomon! I will decide the fate of all!!!”

“What if someone doesn’t want you to decide their fate?”

“Well, they’ll have no choice! Once I have my wishes, my will shall prevail!” Megan’s eyes gleamed as she looked eagerly toward the glade where they had seen the Elf maiden dancing.

Polly sighed and shifted away from her sister. “You were right,” she said, whispering so that her sister couldn’t hear.

A chiming, silvery voice answered her from the shadows of the oak tree beside her. “Yes, but there is no helping it; she is right. A wish must be granted; it is May Eve.”

“Must it be my sister’s wish?”

“You each get a wish, because you both saw me in the glade.”

Polly thought for a moment. “Could my wish be that we had never seen you in the glade?”

There was a pause, and all Polly could hear was crickets tuning up for their evening serenade. But then came a peal of merry laughter from the shadows.

“Yes, of course!” came the answer. “But, your sister would still be granted a wish, regardless.”

Polly thought for a moment. “OK, then that’s what I’d like to wish for…that we had never seen you tonight.”

o o o

“I hate these things!” said Megan, slapping at her neck.

“What things?!” asked Polly. She felt disoriented…dizzy, even.

“The mosquitoes of course!” Megan slapped again at her neck. “And I’m tired of waiting for Fairies! I’m going in!” She stood up and brushed herself off.

“So you don’t think they’re going to come at all?” asked Polly.

“I don’t care if they do! I’m going home!”

“OK,” said Polly, standing up as well. “I’ll come too….”

“Ouch!” said Megan. “These mosquitoes are awful! I wish we’d have just one summer without them!”

Polly didn’t remember anything significant about her sister’s comment until summer ended that year. It was in autumn that it occurred to her that the only mosquito bites she and her sister had gotten all year long had been on May Eve.

On Fairy Tales

(A rhapsody on themes from G.K. Chesterton & J.R.R. Tolkien) by Jef Murray

As a Catholic artist and storyteller, what interests me most are those things that help us all to make sense of the world around us. And what most helps us to make sense of the world, and our lives in it, are the stories that have been handed down to us throughout the ages.

What are those stories? They are among the oldest bits of pathos, humor, and wisdom that have survived; the tales that we hear in our earliest years of life. They’re the ones we’re read as children, but the ones that, to our folly, we often forget or disparage as adults.

G. K. Chesterton tells us “My first and last philosophy, that which I believe in with unbroken certainty, I learnt in the nursery.” “I left the fairy tales lying on the floor of the nursery, and I have not found any books so sensible since.”

Our greatest inspirations come from the stories that we hear, or see performed, or read, or view (captured in paint or charcoal, or stone). And whether these are parables told from Scripture, legends, or epic dramas and adventures, these “lies breathed through silver”, as C.S. Lewis once called them, continue to inspire us, and continue to be told from each generation to the next.

Why is that? I’d like to spend some time exploring that question.

Uncle Fred vs. Elfland

But, aren’t Fairy Tales just for children? Aren’t they simply something that we are told to entertain us? Something that we outgrow once we become better able understand the “real world”?

G.K. Chesterton suggests that we all, as adults, have likely had the experience of some avuncular authority figure, such as a stodgy old family friend or our weird Uncle Alfred, telling us something along the lines of “Yes, yes, that’s all very well and good, my lad, and I used to enjoy a good Fairy Tale, too, when I was your age. But, you know, once you become an adult, you learn to lay aside such frivolities and get on with the world as it really is; you learn to make compromises in order to become a decent and practical fellow.”

Such was the sort of advice I was given, and whether you hear it from your Uncle Alfred, your Aunt Bessie, or from the halls of Congress, the fact is that it’s just so much rubbish; but that, you must discover for yourself.

Like Chesterton, the more I’ve looked at the “real world” as an adult, the more tightly I’ve clung to the truths I learned as a child, and the less convinced I’ve become of the “reality” of the day to day “practical world” that we’re so often assured we must embrace.

When we look at how the world is presented to us by Uncle Fred, what we’re given is a clinical, cold, uncaring universe that stretches out in all directions. We have cited to us the “laws” of physics, of economics, of aesthetics, of politics; the same sort of laws that govern the movements of machinery, and therefore, the same sort of laws that suggest the “real world” is, in fact, a vast, dead thing; a great rambling automobile plunging headlong down the highway, with no one at the wheel.

Well, as it turns out, Fairy Tales also have their own laws, and very peculiar ones at that, but they’re of a very different sort, and we’ll get to those shortly.

In the meantime, the fact of the matter, and something that is never addressed by Uncle Fred, is why the world is as he claims it to be? Why does the sun rise each morning, in glorious splendor? Why does the scent of a rose inspire us with reveries on love, on beauty, and on heaven itself?

Uncle Fred will insist that the sun is simply something akin to a clock; it comes ‘round each day at the same time because it’s a lifeless blob of molecules obeying the universal laws of astrophysics. It is a mass of ignited hydrogen with such and such an amount of gravity and so much radiant output (at such and such frequencies of the spectrum) emitted per second. And Uncle Fred, or his scientist or economist friends, will go on to explain every facet of our earth, every comet, every tree, every meteor, every animal, every star, every solar system, every galaxy, and the cosmos as a whole in similar dreary terms.

But Fairy Tales suggest to us a very different way of looking things. They teach us that the world is, in fact, a magical and seemingly inexplicable place. They nurture in us a sense of wonder and astonishment at the complexity and beauty of all things; astonishment that belies Uncle Fred’s smug statements. Such wonder is readily experienced by all of us as children, although many of us may have had our “astonishment muscles” atrophy as adults. Fairy tales, however, have a unique capacity to “wake us up” again.

Why, for instance, should the sun be golden and the grass green? In Faerie, they may be some entirely different combination! And when we “return” from a Fairy Tale, wherein the sun is, perhaps, blue, and the grass violet, we notice, as if for the first time, the very peculiarity of our own gilded star and the deep verdure of our grasses. We once again see them for what they are rather than for what Uncle Fred tells us; and what they are, is magical.

C.S. Lewis, in his book “The Voyage of the Dawn Treader”, underscores this difference in looking at things in the following exchange between Eustace, the youthful acolyte of our secular, mechanistic Uncle Fred, and Ramandu, who is a “star at rest”, retired from the sky for a brief period (in the lifetime of stars, at least) before rising once more into the heavens:

“In our world,” says Eustace, “a star is a huge ball of flaming gas.”

“Even in your world, my son,” says Ramandu,”that is not what a star is, but only what it is made of.”

What is a star in our world? Ask any child: it is a jewel twinkling in the deep blue seas of the heavens; it is an angel riding high over the horizon; it is Earendil the Mariner sailing his enchanted ship, Vingilot; it is a prayer winging its way to God. In other words, a star is magical. It ever was, and it ever shall be.

Magic & Meaning

So, if the world is magical, then there must be some method to its madness. Magic, after all, has its own way of operating, as any child will tell you. Every child knows, for instance, that a kiss is a magical thing. It can heal a scraped knee. It can also change a frog into a prince. It can do other things too, and as we begin to look at the magic of Fairy Tales, and begin to see how that magic is reflected in our own world, we can tease out some of the ways that magic truly operates.

What are a few of the lessons that we can learn from Fairy Tales? That is, what is spelled out by the magic we encounter in them?

What lesson, for instance, comes from story of Pinocchio? That the truth will set us free.

What might be learned from Cinderella? Simply that the humble shall be exalted and the proud brought low.

What lesson comes from Beauty and the Beast? That it is love itself that transforms us from beasts into men.

And what about our magic kiss? Aside from turning frogs into princes, Sleeping Beauty teaches us that a kiss is so magical that it can soften death itself into a sort of a sleep, from which one might be awakened.

What lesson comes from The Hobbit? Or from the Icelandic tales of Sigurd and Fafnir the dragon? First, that there are dragons in th: world; hideous, cunning monsters that devour all in their paths. But we needn’t rely on Fairy Tales to teach us that; we simply need to heed the nightly newscast. So, what is missing from the nightly newscast that we learn in Fairy Tales? Simply this: that despite their strength and cunning, dragons can be slain.

All of these lessons have meaning; they’re not arbitrary. They define how magic works, and that same magic works in our world just as it works in the world of Faerie. The sun rises in our world, just as in the world of Faerie, because it is enchanted. And it rises the same each day because, just like a little child with boundless energy, repetition in Fairyland (“Do it again, Daddy!!!”) is the sign of things that are good, that are wondrous.

Every evening, one can find some spot on earth to stand and view the sunset, and every evening, it is glorious…somewhere. Why wouldn’t the sun come up each morning and go down each evening, every evening, when the show is so magnificent? Why don’t we recognize that the fact that the forests grow and the clouds sail all day long are both splendid?! If we were to design such things just because they were magnificent and meant to be enjoyed, we could do no better!

But, aren’t they meant to be enjoyed? Aren’t they are meant to be noticed? In other words, aren’t they here for a purpose? That of course begs the question…if something has a purpose, did not someone design them to have that purpose? That is to say, if the world is magical…then does that not mean that there must be a magician?

The Fiats of Faerie

The primary difference between the way I looked at the world as a child and the way I look at it as an adult is that, as a child, I always demanded justice: I wanted the wicked witch to die! I insisted that my heroes must never falter! But, as an adult, I find that I am now more drawn to mercy: the wicked witch may yet repent; and some of the greatest heroes do, in fact, falter. More importantly, I know my own weaknesses as an adult better (I hope!) than I knew them as a child.

But I want to get us back to the peculiar laws of fairy tales that I alluded to earlier. Because, although we’ve said that the world is glorious, it is not without flaws…or so it might seem. But the peculiar laws of Faerie actually help us to make sense of those “flaws”.

We’ve said that in Fairy Tales we learn that dragons can be slain, but, in truth, there are very particular ways that they can be slain, and only those. Typically they require the efforts of a hero, often wielding a very special sort of holy or blessed weapon, and wielded for a very noble and/or selfless cause (such as the saving of the life of a maiden). Without these, the magic required to slay the dragon will not function.

As G.K. Chesterton points out, and J.R.R. Tolkien affirms, in many if not most fairy tales, there are thus conditions, or requirements, that must be met in order for the greatest good, the desired happy ending we all yearn for, to be achieved. These conditions may be as arbitrary as you’d like, but they are inevitably there.

Chesterton puts it this way: “The note of the fairy utterance always is, ‘You may live in a palace of gold and sapphire, if you do not say the word “cow”’; or ‘You may live happily with the King’s daughter, if you do not show her an onion.’ The vision always hangs upon a veto. All the dizzy and colossal things conceded depend upon one small thing withheld.”

Tolkien refers to this as “The Ban”, and he reminds us that all of Elfland is full of them; in fact, all of Elfland requires them. Happiness, we are told, can hinge upon something as seemingly inconsequential as releasing a fox caught in a trap, or of not placing a magic ring upon one’s finger.

Our world, as it happens, is just the same. Our great religious traditions give us similar “conditionals”, and they may sometimes seem to be just as arbitrary as any Ban given in a Fairy Tale. Thou shalt honor thy parents, thou shalt not covet, thou shalt not bear false witness, etc. We’re assured by Uncle Fred that we can ignore such conditions, or that we can tiptoe around them as needed. But when such conditions are ignored in Fairy Tales, inevitably, bad things happen; if we accept that the world we inhabit also is magical, then we, too, ignore its “conditionals” at our own great peril.

But, we need not ignore them. The world is beautiful, is it not? It is magical! Too magical to risk! Why would we wish to?!

Who among us has never been in love? When one is in love, does not the very light of day appear bursting with glory? Don’t we hear the singing of the birds in the trees (multicolored wonders that they are!) and know that theirs is a song of praise; of love and of life? Why would any of us ever want to risk such things?!

“Look about you,” says Justin Playfair, the character who believes himself to be Sherlock Holmes in the movie “They Might Be Giants”. “This is paradise. It’s hard to find, I’ll grant you, but it is here. Under our feet, beneath the surface, all around us is everything we want. The earth is shining under the soot. We are all fools. Moriarty has made fools of all of us!”

We are all fools; that is, until Fairy Tales remind us of how peculiarly beautiful, how marvelous, how extraordinarily unlikely and magical, is the world that we have been given, and how important it is not to lose it all to Uncle Fred!

Becoming as Little Children

When we begin to realize how incredibly unlikely it is that any of us should be in this world, reading these words, perhaps enjoying the sunshine streaming through the window or hearing the drumming of rain on the rooftops…that is, when we allow the scales to begin to fall from our eyes a bit, there is an almost instantaneous desire to give thanks for what we have. And that’s one of the most important points of Fairy tales; they give us opportunities for recovery, and for gratitude.

By recovery, J.R.R. Tolkien refers to the capacity for Fairy Tales to restore within us that sense of wonder that we so often lose; recovery is the long sought-after escape for the prisoner, from the bleak walls of an endlessly-stretching dead universe, and equally empty, dead, and meaningless pursuits.

When the scales fall from our eyes, when we begin to see the glimmers of meaning behind the magic of the everyday world, we want to know the Maker of that world and that meaning better; we want to thank Him for the beauty and magic of it all.

Now, I’m no Pollyanna. Nothing that I’m saying today should suggest to anyone that life is nothing but roses and chocolates. But neither is it the dead, sterile and meaningless practical hell so often suggested by Uncle Fred. Many of us suffer each day, even each moment, with physical ailments, with regrets, with anxiety about the future. Many of us are in constant pain. But, that doesn’t minimize the wonders around us; in fact, it can make them just that much more important. In the best of Fairy Tales, the hero must always suffer in order for his ultimate triumph and happiness to have any real value.

But beyond the lovely glistering of fairy dust at each new dawn, there’s something else behind all of the Fairy Tales, something that speaks of a Truth that is almost too glorious and good to be true.

According to J.R.R. Tolkien, the most important element in all of the greatest of Fairy Tales is the recurrence of something he dubbed the “Eucatastrophe”. The Eucatastrophe is a sudden turning point in a tale, the point when all seems lost, and yet, beyond all hope, beyond all prayer, the good triumphs; the just and the worthy prevail, and evil, death, and darkness are vanquished.

The more traditional name for Eucatastrophe is “the happy ending”. But, by the term “Eucatastrophe”, Tolkien wanted to point out to us the very happiest of endings that we encounter in fairy tales: just when Snow White is being carried away, lifeless, in her coffin, the bearers stumble, and the piece of poisoned apple is dislodged from her throat; just when the dragon is destroying Lake Town, with his last arrow, Bard the Bowmen strikes the beast in the only spot where he is vulnerable; just when Beauty finally realizes that she loves the Beast, but finds him dying, it is her remorse and love that bring him back to life; just when the men of the west have been surrounded by the hordes of Sauron, the One Ring is cast into the fires of Mount Doom, and the Dark Lord is destroyed utterly.

These are all Eucatastrophes. They are the prevailing of the good, the worthy, the noble, against the so-called mindlessness of an empty, meaningless world. They aren’t “practical”; but they resonate with us for the precise reason that we know them, deeply, to be true.

J.R.R. Tolkien, G.K. Chesterton, and C.S. Lewis would all have been the first to declare that, if the world is magical, if it is more like a story than a meaningless jumble of random events, then there must be a storyteller. And as the Eucatastrophe is the hallmark of every great Fairy Tale, it is also the hallmark of the greatest Story that we know, and of the greatest Storyteller.

Fairy tales are written with words. But the great Storyteller writes with history itself. Fairy Tales have been handed down since the dawn of humankind, and they have all contained this one marvelous element: of Eucatastrophe. But, in a world that has real meaning, all of these tales have merely prefigured or echoed the one very special Eucatastrophe that was written in deeds rather than in words: the Fairy Tale-come-to-life of the death and resurrection of Christ.

Consider, for a moment. Who among us, hearing the story of Christ for the first time, with the ears of innocence and childhood, would not fervently wish for it to be true? Who among even the most practical of atheists would not love to believe it, if only he could?

The story has all of the elements of the very best Fairy Tale you could possibly imagine; the birth and growth into wisdom and adulthood of someone entirely good, who seeks to liberate a land filled with disease, death, and despair; the healing of thousands by this man, and the bringing of hope to others; the scheming of those who were jealous of him, and their seeming triumph in destroying him – only to have that very death itself lead to the triumphant Return of the King, because His love was stronger than the gates of hell and death itself.

What a marvelous story! And yet…it really happened.

Eucatastrophe, then, is not just some literary device. True, it is a promise made in our most cherished childhood tales, but it is also one that is completely fulfilled in the Gospels. The Storyteller enters His own tale, out of love, in order to bring Goodness, Truth, and Beauty to a world in despair.

Conclusion

I started out asking “Why fairy tales?” That is, what’s the fuss? Why would any artist be so focused on things that are the stuff of childhood legends and fantasies? More than that, why would any of the rest of us want to spend time reading or dwelling on such things?

The answer that I hope I’ve provided, is that Fairy Tales are not “lies breathed through silver”, as C.S. Lewis once called them, but the deepest of Truths bedecked in jewels and glory. They are powerful medicine, but they rest sweet on the tongue, that their message can thus work its magic upon us.

C.S. Lewis once spoke of Fairy Tales being the best means of getting past our “watchful dragons”: those beasts that stand at the threshold of our souls, guarding us against silly childhood notions and enforcing the dictums of our dear, secular Uncle Fred. Fairy tales slip past those dragons, and the Truths that they contain are thus safely tucked away for us to recall in our darkest hours.

“If you want your children to be intelligent,” advised Albert Einstein, “read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.”

So, what are the truths we’ve learned from the realm of Faerie? That the world is a magical place; that it has meaning, because it was created by Someone who instilled it with meaning; that the world is wildly beautiful, despite its flaws; and that the proper response to it and to its Maker is to become as little children: to open our eyes and to trust in the One who has given all of it to us, out of love.

It is my hope that some of these thoughts might re-awaken your own sense of wonder, and you own capacity for hope, for trust, and for the opportunity to look around you once more with fresh eyes.

Mystical Realms Newsletter for April 2014

Greetings!

And welcome to my newsletter for April, 2014! Please feel free to forward this to anyone you think would be interested in keeping up with me! To receive these newsletters regularly, please drop me an email or subscribe online from my website (http://www.JefMurray.com ) or at:http://groups.google.com/group/Mystical_Realms . Notices of events and items of interest are at the bottom of this email.

Pitchers ===============

• A new, revised and expanded edition of Seer: A Wizard’s Journal has been announced and will be available for sale very soon! The 2nd edition of this collection of tales, poetry, images and reflections sports a new cover, many interior illustrations that are now reproduced in full colour, plus two “follow on” tales to the opening story, The Watchman, that more fully introduce characters that appear regularly throughout the remainder of the book. For more information, see:http://olorispublishing.mymiddleearth.com/2014/03/25/oloris-publishing-announces-expanded-version-of-seer-a-wizards-journal-by-jef-murray/

• For those who have requested it, I’ve begun adding prices to those original paintings that are still available for purchase on my website, beginning with the most recent. Updating my gallery pages to include prices will be an ongoing process. If you need to know the status and/or price of a work that does not yet have a price listed, please contact me directly and I’ll add that information. All original paintings and sketches can be shipped internationally.

Prospects ===================

• The third great gathering of Tolkien fans in Kentucky is being planned for September, 2014! A Long Expected Party 3 (acronym “AL3P) is completely booked, but you can still be put on the waiting list to attend on-site. You can also still register, and offsite lodging is available. I’m delighted to announce that I will be one of three guests at the event, along with Dr. Michael Drout and Dr. Amy Sturgis. For more information, see: http://www.alep-ky.us/

Ponderings ==============

On Fairy Tales

(A rhapsody on themes from G.K. Chesterton & J.R.R. Tolkien) by Jef Murray

As a Catholic artist and storyteller, what interests me most are those things that help us all to make sense of the world around us. And what most helps us to make sense of the world, and our lives in it, are the stories that have been handed down to us throughout the ages.

What are those stories? They are among the oldest bits of pathos, humor, and wisdom that have survived; the tales that we hear in our earliest years of life. They’re the ones we’re read as children, but the ones that, to our folly, we often forget or disparage as adults.

G. K. Chesterton tells us “My first and last philosophy, that which I believe in with unbroken certainty, I learnt in the nursery.” “I left the fairy tales lying on the floor of the nursery, and I have not found any books so sensible since.”

Our greatest inspirations come from the stories that we hear, or see performed, or read, or view (captured in paint or charcoal, or stone). And whether these are parables told from Scripture, legends, or epic dramas and adventures, these “lies breathed through silver”, as C.S. Lewis once called them, continue to inspire us, and continue to be told from each generation to the next.

Why is that? I’d like to spend some time exploring that question.

Uncle Fred vs. Elfland

But, aren’t Fairy Tales just for children? Aren’t they simply something that we are told to entertain us? Something that we outgrow once we become better able understand the “real world”?

G.K. Chesterton suggests that we all, as adults, have likely had the experience of some avuncular authority figure, such as a stodgy old family friend or our weird Uncle Alfred, telling us something along the lines of “Yes, yes, that’s all very well and good, my lad, and I used to enjoy a good Fairy Tale, too, when I was your age. But, you know, once you become an adult, you learn to lay aside such frivolities and get on with the world as it really is; you learn to make compromises in order to become a decent and practical fellow.”

Such was the sort of advice I was given, and whether you hear it from your Uncle Alfred, your Aunt Bessie, or from the halls of Congress, the fact is that it’s just so much rubbish; but that, you must discover for yourself.

Like Chesterton, the more I’ve looked at the “real world” as an adult, the more tightly I’ve clung to the truths I learned as a child, and the less convinced I’ve become of the “reality” of the day to day “practical world” that we’re so often assured we must embrace.

When we look at how the world is presented to us by Uncle Fred, what we’re given is a clinical, cold, uncaring universe that stretches out in all directions. We have cited to us the “laws” of physics, of economics, of aesthetics, of politics; the same sort of laws that govern the movements of machinery, and therefore, the same sort of laws that suggest the “real world” is, in fact, a vast, dead thing; a great rambling automobile plunging headlong down the highway, with no one at the wheel.

Well, as it turns out, Fairy Tales also have their own laws, and very peculiar ones at that, but they’re of a very different sort, and we’ll get to those shortly.

In the meantime, the fact of the matter, and something that is never addressed by Uncle Fred, is why the world is as he claims it to be? Why does the sun rise each morning, in glorious splendor? Why does the scent of a rose inspire us with reveries on love, on beauty, and on heaven itself?

Uncle Fred will insist that the sun is simply something akin to a clock; it comes ‘round each day at the same time because it’s a lifeless blob of molecules obeying the universal laws of astrophysics. It is a mass of ignited hydrogen with such and such an amount of gravity and so much radiant output (at such and such frequencies of the spectrum) emitted per second. And Uncle Fred, or his scientist or economist friends, will go on to explain every facet of our earth, every comet, every tree, every meteor, every animal, every star, every solar system, every galaxy, and the cosmos as a whole in similar dreary terms.

But Fairy Tales suggest to us a very different way of looking things. They teach us that the world is, in fact, a magical and seemingly inexplicable place. They nurture in us a sense of wonder and astonishment at the complexity and beauty of all things; astonishment that belies Uncle Fred’s smug statements. Such wonder is readily experienced by all of us as children, although many of us may have had our “astonishment muscles” atrophy as adults. Fairy tales, however, have a unique capacity to “wake us up” again.

Why, for instance, should the sun be golden and the grass green? In Faerie, they may be some entirely different combination! And when we “return” from a Fairy Tale, wherein the sun is, perhaps, blue, and the grass violet, we notice, as if for the first time, the very peculiarity of our own gilded star and the deep verdure of our grasses. We once again see them for what they are rather than for what Uncle Fred tells us; and what they are, is magical.

C.S. Lewis, in his book “The Voyage of the Dawn Treader”, underscores this difference in looking at things in the following exchange between Eustace, the youthful acolyte of our secular, mechanistic Uncle Fred, and Ramandu, who is a “star at rest”, retired from the sky for a brief period (in the lifetime of stars, at least) before rising once more into the heavens:

“In our world,” says Eustace, “a star is a huge ball of flaming gas.”

“Even in your world, my son,” says Ramandu,”that is not what a star is, but only what it is made of.”

What is a star in our world? Ask any child: it is a jewel twinkling in the deep blue seas of the heavens; it is an angel riding high over the horizon; it is Earendil the Mariner sailing his enchanted ship, Vingilot; it is a prayer winging its way to God. In other words, a star is magical. It ever was, and it ever shall be.

Magic & Meaning

So, if the world is magical, then there must be some method to its madness. Magic, after all, has its own way of operating, as any child will tell you. Every child knows, for instance, that a kiss is a magical thing. It can heal a scraped knee. It can also change a frog into a prince. It can do other things too, and as we begin to look at the magic of Fairy Tales, and begin to see how that magic is reflected in our own world, we can tease out some of the ways that magic truly operates.

What are a few of the lessons that we can learn from Fairy Tales? That is, what is spelled out by the magic we encounter in them?

What lesson, for instance, comes from story of Pinocchio? That the truth will set us free.

What might be learned from Cinderella? Simply that the humble shall be exalted and the proud brought low.

What lesson comes from Beauty and the Beast? That it is love itself that transforms us from beasts into men.

And what about our magic kiss? Aside from turning frogs into princes, Sleeping Beauty teaches us that a kiss is so magical that it can soften death itself into a sort of a sleep, from which one might be awakened.

What lesson comes from The Hobbit? Or from the Icelandic tales of Sigurd and Fafnir the dragon? First, that there are dragons in th: world; hideous, cunning monsters that devour all in their paths. But we needn’t rely on Fairy Tales to teach us that; we simply need to heed the nightly newscast. So, what is missing from the nightly newscast that we learn in Fairy Tales? Simply this: that despite their strength and cunning, dragons can be slain.

All of these lessons have meaning; they’re not arbitrary. They define how magic works, and that same magic works in our world just as it works in the world of Faerie. The sun rises in our world, just as in the world of Faerie, because it is enchanted. And it rises the same each day because, just like a little child with boundless energy, repetition in Fairyland (“Do it again, Daddy!!!”) is the sign of things that are good, that are wondrous.

Every evening, one can find some spot on earth to stand and view the sunset, and every evening, it is glorious…somewhere. Why wouldn’t the sun come up each morning and go down each evening, every evening, when the show is so magnificent? Why don’t we recognize that the fact that the forests grow and the clouds sail all day long are both splendid?! If we were to design such things just because they were magnificent and meant to be enjoyed, we could do no better!

But, aren’t they meant to be enjoyed? Aren’t they are meant to be noticed? In other words, aren’t they here for a purpose? That of course begs the question…if something has a purpose, did not someone design them to have that purpose? That is to say, if the world is magical…then does that not mean that there must be a magician?

The Fiats of Faerie

The primary difference between the way I looked at the world as a child and the way I look at it as an adult is that, as a child, I always demanded justice: I wanted the wicked witch to die! I insisted that my heroes must never falter! But, as an adult, I find that I am now more drawn to mercy: the wicked witch may yet repent; and some of the greatest heroes do, in fact, falter. More importantly, I know my own weaknesses as an adult better (I hope!) than I knew them as a child.

But I want to get us back to the peculiar laws of fairy tales that I alluded to earlier. Because, although we’ve said that the world is glorious, it is not without flaws…or so it might seem. But the peculiar laws of Faerie actually help us to make sense of those “flaws”.

We’ve said that in Fairy Tales we learn that dragons can be slain, but, in truth, there are very particular ways that they can be slain, and only those. Typically they require the efforts of a hero, often wielding a very special sort of holy or blessed weapon, and wielded for a very noble and/or selfless cause (such as the saving of the life of a maiden). Without these, the magic required to slay the dragon will not function.

As G.K. Chesterton points out, and J.R.R. Tolkien affirms, in many if not most fairy tales, there are thus conditions, or requirements, that must be met in order for the greatest good, the desired happy ending we all yearn for, to be achieved. These conditions may be as arbitrary as you’d like, but they are inevitably there.

Chesterton puts it this way: “The note of the fairy utterance always is, ‘You may live in a palace of gold and sapphire, if you do not say the word “cow”’; or ‘You may live happily with the King’s daughter, if you do not show her an onion.’ The vision always hangs upon a veto. All the dizzy and colossal things conceded depend upon one small thing withheld.”

Tolkien refers to this as “The Ban”, and he reminds us that all of Elfland is full of them; in fact, all of Elfland requires them. Happiness, we are told, can hinge upon something as seemingly inconsequential as releasing a fox caught in a trap, or of not placing a magic ring upon one’s finger.

Our world, as it happens, is just the same. Our great religious traditions give us similar “conditionals”, and they may sometimes seem to be just as arbitrary as any Ban given in a Fairy Tale. Thou shalt honor thy parents, thou shalt not covet, thou shalt not bear false witness, etc. We’re assured by Uncle Fred that we can ignore such conditions, or that we can tiptoe around them as needed. But when such conditions are ignored in Fairy Tales, inevitably, bad things happen; if we accept that the world we inhabit also is magical, then we, too, ignore its “conditionals” at our own great peril.

But, we need not ignore them. The world is beautiful, is it not? It is magical! Too magical to risk! Why would we wish to?!

Who among us has never been in love? When one is in love, does not the very light of day appear bursting with glory? Don’t we hear the singing of the birds in the trees (multicolored wonders that they are!) and know that theirs is a song of praise; of love and of life? Why would any of us ever want to risk such things?!

“Look about you,” says Justin Playfair, the character who believes himself to be Sherlock Holmes in the movie “They Might Be Giants”. “This is paradise. It’s hard to find, I’ll grant you, but it is here. Under our feet, beneath the surface, all around us is everything we want. The earth is shining under the soot. We are all fools. Moriarty has made fools of all of us!”

We are all fools; that is, until Fairy Tales remind us of how peculiarly beautiful, how marvelous, how extraordinarily unlikely and magical, is the world that we have been given, and how important it is not to lose it all to Uncle Fred!

Becoming as Little Children

When we begin to realize how incredibly unlikely it is that any of us should be in this world, reading these words, perhaps enjoying the sunshine streaming through the window or hearing the drumming of rain on the rooftops…that is, when we allow the scales to begin to fall from our eyes a bit, there is an almost instantaneous desire to give thanks for what we have. And that’s one of the most important points of Fairy tales; they give us opportunities for recovery, and for gratitude.

By recovery, J.R.R. Tolkien refers to the capacity for Fairy Tales to restore within us that sense of wonder that we so often lose; recovery is the long sought-after escape for the prisoner, from the bleak walls of an endlessly-stretching dead universe, and equally empty, dead, and meaningless pursuits.

When the scales fall from our eyes, when we begin to see the glimmers of meaning behind the magic of the everyday world, we want to know the Maker of that world and that meaning better; we want to thank Him for the beauty and magic of it all.

Now, I’m no Pollyanna. Nothing that I’m saying today should suggest to anyone that life is nothing but roses and chocolates. But neither is it the dead, sterile and meaningless practical hell so often suggested by Uncle Fred. Many of us suffer each day, even each moment, with physical ailments, with regrets, with anxiety about the future. Many of us are in constant pain. But, that doesn’t minimize the wonders around us; in fact, it can make them just that much more important. In the best of Fairy Tales, the hero must always suffer in order for his ultimate triumph and happiness to have any real value.

But beyond the lovely glistering of fairy dust at each new dawn, there’s something else behind all of the Fairy Tales, something that speaks of a Truth that is almost too glorious and good to be true.

According to J.R.R. Tolkien, the most important element in all of the greatest of Fairy Tales is the recurrence of something he dubbed the “Eucatastrophe”. The Eucatastrophe is a sudden turning point in a tale, the point when all seems lost, and yet, beyond all hope, beyond all prayer, the good triumphs; the just and the worthy prevail, and evil, death, and darkness are vanquished.

The more traditional name for Eucatastrophe is “the happy ending”. But, by the term “Eucatastrophe”, Tolkien wanted to point out to us the very happiest of endings that we encounter in fairy tales: just when Snow White is being carried away, lifeless, in her coffin, the bearers stumble, and the piece of poisoned apple is dislodged from her throat; just when the dragon is destroying Lake Town, with his last arrow, Bard the Bowmen strikes the beast in the only spot where he is vulnerable; just when Beauty finally realizes that she loves the Beast, but finds him dying, it is her remorse and love that bring him back to life; just when the men of the west have been surrounded by the hordes of Sauron, the One Ring is cast into the fires of Mount Doom, and the Dark Lord is destroyed utterly.

These are all Eucatastrophes. They are the prevailing of the good, the worthy, the noble, against the so-called mindlessness of an empty, meaningless world. They aren’t “practical”; but they resonate with us for the precise reason that we know them, deeply, to be true.

J.R.R. Tolkien, G.K. Chesterton, and C.S. Lewis would all have been the first to declare that, if the world is magical, if it is more like a story than a meaningless jumble of random events, then there must be a storyteller. And as the Eucatastrophe is the hallmark of every great Fairy Tale, it is also the hallmark of the greatest Story that we know, and of the greatest Storyteller.

Fairy tales are written with words. But the great Storyteller writes with history itself. Fairy Tales have been handed down since the dawn of humankind, and they have all contained this one marvelous element: of Eucatastrophe. But, in a world that has real meaning, all of these tales have merely prefigured or echoed the one very special Eucatastrophe that was written in deeds rather than in words: the Fairy Tale-come-to-life of the death and resurrection of Christ.

Consider, for a moment. Who among us, hearing the story of Christ for the first time, with the ears of innocence and childhood, would not fervently wish for it to be true? Who among even the most practical of atheists would not love to believe it, if only he could?

The story has all of the elements of the very best Fairy Tale you could possibly imagine; the birth and growth into wisdom and adulthood of someone entirely good, who seeks to liberate a land filled with disease, death, and despair; the healing of thousands by this man, and the bringing of hope to others; the scheming of those who were jealous of him, and their seeming triumph in destroying him – only to have that very death itself lead to the triumphant Return of the King, because His love was stronger than the gates of hell and death itself.

What a marvelous story! And yet…it really happened.

Eucatastrophe, then, is not just some literary device. True, it is a promise made in our most cherished childhood tales, but it is also one that is completely fulfilled in the Gospels. The Storyteller enters His own tale, out of love, in order to bring Goodness, Truth, and Beauty to a world in despair.

Conclusion

I started out asking “Why fairy tales?” That is, what’s the fuss? Why would any artist be so focused on things that are the stuff of childhood legends and fantasies? More than that, why would any of the rest of us want to spend time reading or dwelling on such things?

The answer that I hope I’ve provided, is that Fairy Tales are not “lies breathed through silver”, as C.S. Lewis once called them, but the deepest of Truths bedecked in jewels and glory. They are powerful medicine, but they rest sweet on the tongue, that their message can thus work its magic upon us.

C.S. Lewis once spoke of Fairy Tales being the best means of getting past our “watchful dragons”: those beasts that stand at the threshold of our souls, guarding us against silly childhood notions and enforcing the dictums of our dear, secular Uncle Fred. Fairy tales slip past those dragons, and the Truths that they contain are thus safely tucked away for us to recall in our darkest hours.

“If you want your children to be intelligent,” advised Albert Einstein, “read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.”

So, what are the truths we’ve learned from the realm of Faerie? That the world is a magical place; that it has meaning, because it was created by Someone who instilled it with meaning; that the world is wildly beautiful, despite its flaws; and that the proper response to it and to its Maker is to become as little children: to open our eyes and to trust in the One who has given all of it to us, out of love.

It is my hope that some of these thoughts might re-awaken your own sense of wonder, and you own capacity for hope, for trust, and for the opportunity to look around you once more with fresh eyes.

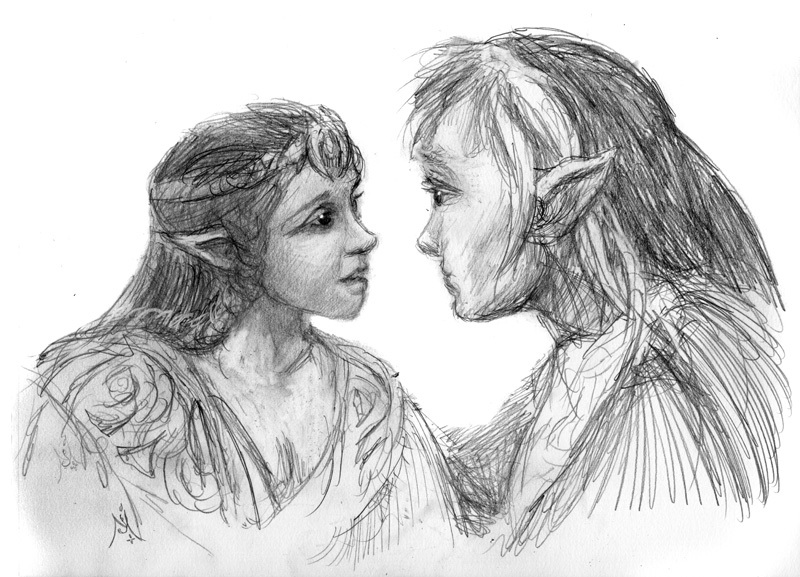

Fair Folk

All Souls’ Day (Frodo in the Dead Marshes)

Mystical Realms Newsletter for March, 2014

Greetings!

And welcome to my newsletter for March, 2014! Please feel free to forward this to anyone you think would be interested in keeping up with me! To receive these newsletters regularly, please drop me an email or subscribe online from my website (http://www.JefMurray.com ) or at: http://groups.google.com/group/Mystical_Realms . Notices of events and items of interest are at the bottom of this email.

Pitchers ===============

• For those who have requested it, I’ve begun adding prices to those original paintings that are currently available for purchase on my website (www.JefMurray.com), beginning with the most recent. Updating my gallery pages, including prices for original sketches as well as paintings, will be an ongoing process, and I’ll be adding prices as I am able. If you need to know the status and/or price of an original work that does not yet have a price, please contact me directly and I’ll add that information. All works can be shipped internationally.

• I’ve added 3 new painting images to my website at www.JefMurray.com . These include The Arkenstone, A Canticle for Elessar, and Piper of Dreams. The first of these can be found in my Middle-earth->The Third Age->The Hobbit gallery, the second can be found in my Middle-earth->The Third Age->Lord of the Rings gallery, and the third can be found in my Fairy Tales->Paintings gallery. You can also find them all by going to http://www.JefMurray.com and clicking on the “Newest Works->Paintings” link at the top, left.

• In addition to the three paintings, I have added four new graphite sketch images to the Middle-earth, Fairy Tale, and Soul & Spirit sketch galleries. You can see all of the latest together by clicking on the “Newest Works -> Sketches” link at the top, left my home page, www.JefMurray.com .

• The current 1st edition of Seer: A Wizard’s Journal is being reviewed in the upcoming issue of the St. Austin Review (StAR). For more information about StAR, see: www.staustinreview.com. Also, look for news on a new edition of Seer: A Wizard’s Journal soon! Watch this space!

Prospects ===================

• The third great gathering of Tolkien fans in Kentucky is being planned for September, 2014! A Long Expected Party 3 (acronym “AL3P) is completely booked, but you can still be put on the waiting list to attend on-site. You can also still register, and offsite lodging is available. I’m delighted to announce that I will be one of three guests at the event, along with Dr. Michael Drout and Dr. Amy Sturgis. For more information, see: http://www.alep-ky.us/

Ponderings ==============

“It protects you from all physical harm, my dear Sir, and even from death itself; but it cannot protect you from evil,” said the old woman, holding up the necklace to the light. It was fashioned of silver and jet, and the dingy shards of sunlight that struck the petrified stones cast a rainbow of hues against the opposite walls of the shop.

“What do you mean, it can’t protect me from evil itself?What evil exists beyond physical harm?” the young man, well-dressed, and in the latest fashions, smirked slightly.

“Ah!” said the crone, “that, you would know best. But, I’ve had this trinket in my keeping since I was a girl of your age, or even younger. Yet I can assure you that not all evil is physical….”

“Well, be that as it may, I’ll take it, if only as a curiosity to amuse my friends. What will you charge for it?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing?! It is not for sale, then?”

“It is not for sale, but it can be had. Such as this may only be passed on; it cannot be bought. Not for money, anyways.”

“Well, then, must I do something in exchange for it?” the young man began to grow wary.

“Yes, indeed! You must do me a favor; a simple thing, really.”

“And what favor is that?”

“You must bring me a single drop of blood from a child; one of no more than two years of age.”

“What absurd nonsense! Why on earth would I consent to such a thing?”

“Ah, again, you would know best. But, let me demonstrate….” The old woman rose and stepped toward the fireplace. She thrust her hand into the coals and picked one up in her bare hand. Then she turned and walked toward the young man.

“You see what I am holding?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“And you see that I take no harm from the coal?”

“Yes, I see that, too.”

“Well, then, such is the virtue of this necklace that neither coals, nor hail, nor flood can harm me or any who holds it.”

“Ha! Or it could be, woman, that this is just sleight of hand! Here, let me handle that coal that you claim harms you not.”

The crone smiled. “Certainly,” she said, and placed the glowing ember into his palm.

Immediately the young man screamed and flung the cinder away. Sparks flew from the corner where it was cast.

“My God, woman! You’ve maimed me!” he cried, holding up his seared palm.

“Nay, Sir, I’ve but let you observe the power of the necklace. Here, place it about your neck, and you will find that all is healed once more.”

The woman lifted the necklace over his head, and immediately the searing pain in his hand ceased. He held his palm aloft and looked at it; there was no sign of the charring that he had just experienced.

After a few moments of wonder, he looked craftily at the woman. “One drop of blood, you say?”

“Just one,” she responded.

“But…from a child? Must it be from a child?”

“Aye, else it becomes but another trinket. Its power will fade, even from you ere long, unless the pact is made.”

“The pact?”

“Yes, the pact required for you to have it. A single drop of blood from a child…and your own soul in the bargain.”

“I don’t believe in the soul, so that part is easy….”

“Ah! Neither did I, good Sir, neither did I! But, since I’ve held this trinket, I’ve come to,change my mind.”

“That, I shall never do!”

“Then you’re the right one to have her next then, Sir; the necklace, I mean. Sure as I’m a sinner, you are her next owner! But, mark my words, you need not commit your soul at the start; just the drop of blood of an innocent is required. The rest will come in due time….”